COVID-19 and ‘Chasing for Water’: Let’s revisit the Everyday Experiences of Water Access in Poor Urban Spaces.

“……in most parts of our world, people struggle to get regular clean drinking water let alone getting water to wash hands. In my area, we haven’t received water supply from Ghana Water for the past two days. Some people may be privileged to afford alternative water, but what about those who can’t? It is really interesting times ahead…….”

The above is an excerpt from a WhatsApp conversation I had with a friend whilst discussing reported cases of COVID-19 in Ghana. This shifted my attention to write a blog aimed at revisiting the everyday practices and inequalities which characterise water access among the urban poor and vulnerable in Southern cities.

This global pandemic (COVID-19) might partly be considered a WASH disease which requires precautionary measures such as regular hand washing, drinking more water etc. In response to this scare, many Water Service Providers (WSPs) or utilities in developed countries have issued drastic measures with the aim of supplying water 24/7 as well as suspending water shutoffs in the face of COVID-19.

In Detroit USA for instance, it is reported that water will be temporarily restored to thousands of poor residents disconnected due to unpaid bills, as a result of the COVID-19 threat. The Guardian reports that almost 90 cities and states across the USA have suspended water shutoffs for residents unable to afford their bills. About 57 million Americans will be protected from losing their water service during this time.

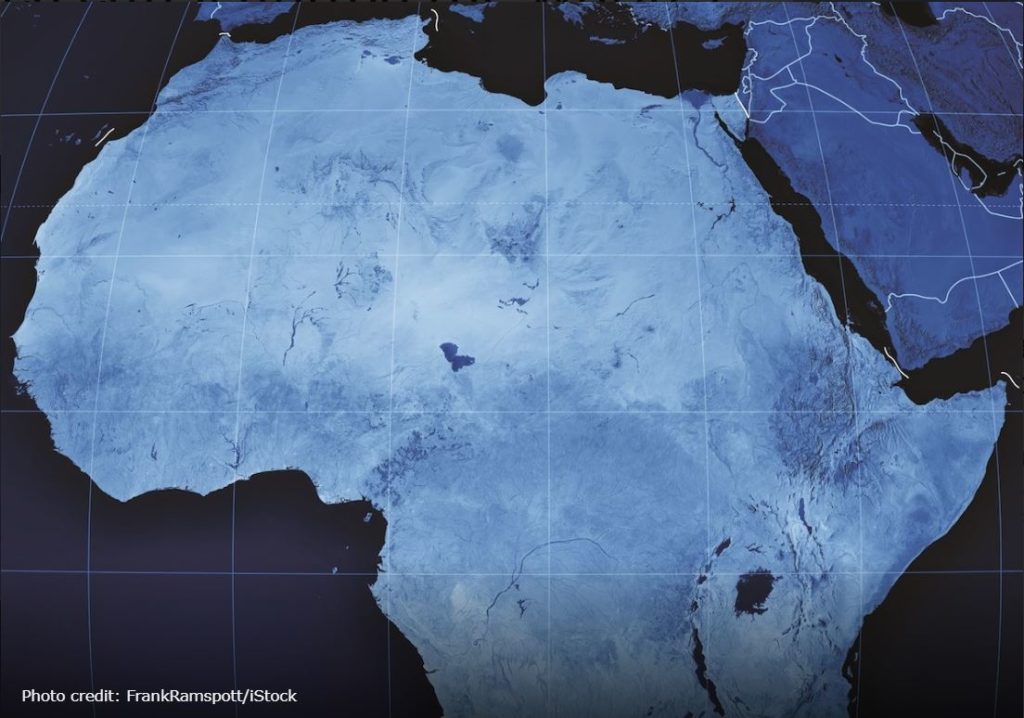

However, should we be more worried about the populations in developing countries who are often confronted with everyday inequalities in water access in light of COVID-19 pandemic? Of course, the emergence of this pandemic will not necessarily mean a move away from the stark inequalities in water flow, quality of water supplied and the frequent and long-lasting cuts in water provision in most Southern cities.

In effect, increasing water shortages, intermittency of water supply, poor infrastructural networks to provide quality drinking water and the spatial splintering that characterise many Southern cities present a challenge towards supressing COVID-19 spread. This question is even tougher for the poorer populations who do not only receive erratic water supply but meet their daily water needs through a dynamic patchwork of sources including tankers, standpipes and sachet or packaged water.

That is, the increased growth of informality and the sprouting of slum communities make residents highly dependent on informal water markets (tankers, vendor) whose quality and cost are often in contestation and doubt. Hence, how do the WHO advised precautionary measures on COVID-19 fit with the everyday practices of those without 24/7 water supply? How do the cost and public health externalities which characterize informal water markets affect the spread or reduction of COVID-19? Does the quest to provide or access water in this dark time compound existing inequalities?

It is not my goal to answer these questions but to provide an avenue to explore these in the spaces of water management and policy especially with regards to the COVID-19 pandemic and other preventable diseases. When clean drinking water is unavailable or runs out, people will resort to unsafe water which is not suitable for the fight against COVID-19.

In Ghana for example, residents in parts of Accra fear high risk of coronavirus infection amidst water rationing. Reports by CitiTV suggest that many households in Accra have had to compromise the directive of frequently washing their hands under running water because of the water rationing. Although the Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL) have advised their consumers to store more water, the unconnected populations might face a higher risk of this infection. An important concern is the fact that social distancing is nearly impossible in many low-income areas where people are likely to queue to access or buy water.

A BBC report in Kenya indicates that hand washing and other personal hygienic practices (such as regular bathing) become difficult for people living in slum -like conditions due to erratic water supply. The bottom-line here is that the poor maybe more vulnerable to this pandemic considering the inequalities that characterise water service provisioning and often lack the means to wash their hands at homes. This is a perfect time to rethink water and sanitation services as well as water use behaviours.

So, what can WSPs and governments do to provide water for the poor?

This question is not new for many policy makers, WSPs, private institutions and national governments. But this crisis provides us an opportunity to remind ourselves on the importance of providing water to the underserved or the poorer populations. Governments and WSPs must invest in and create responsive institutions that help provide services (water and sanitation) to the poor and more importantly during crises.

Low Income Customer Support Units by some utilities and programmes such as Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor in other developing countries are welcome initiatives but there should be long term investment geared towards upscale, resilience and sustainability of services. Perhaps, digital water innovations can be an enabler. For example, adopting models such as those by GSMA and other digital water initiatives may augment water supply to the poor.

In one of my earlier articles, I argued for the adoption of smart water systems for utilities and using ICT based innovations to monitor and regulate the informal water sector. Of course, this not a panacea and should be viewed with caution. Blended finance in providing water should be adapted and adopted where necessary. Obviously, the success of all these will be dependent on proper institutions, political commitment and citizen participation.

COVID-19 is reminding us of the gross inequalities that characterise water and sanitation services and perhaps exposes the lack of preparedness and resilience of the WASH sector in most countries. Also, it reminds us that inclusive water and sanitation services is crucial for all. Let’s use this moment to promote collaborative efforts (institutions, governments, citizens etc) in rethinking and acting for improved WASH services and, responsive water use behaviours by citizens. Education, reliable information and sensitisation programs are key in these trying times.